It would be dishonest to begin this reflection on my journey in ETL401 without admitting my complete ignorance of the role of the Teacher Librarian (TL) prior to the learning encountered in this subject. I selected ETL401 as my (one and only) elective in my Undergraduate Bachelor of Education (Primary) with limited and shallow ideas about what the role of the TL encompassed. My knowledge of what constituted a TL’s role was largely based on my own experiences long ago in Primary School, together with minimal observations in schools on practicums. Ashamedly, I confess that my perception was, for the most part, in keeping with Purcell’s (2010) findings, in that I believed the most important part of the TL’s role was to return, borrow and read books. In saying this, I did not consider the role of the TL insignificant- I admired the ability of TLs to foster a love of reading and to create a colourful, literature-filled learning space. Disturbingly, these misconceptions I held, I found to be common. Fortunately, I can testify that for me, these ignorant, simplistic, preconceived notions were quickly eradicated through engagement in this subject, and replaced with the reality. In undertaking a critical and reflective synthesis on the change in my views of the role of a TL over the last 13 weeks, I have come to realise the radical transformation that occurred in me. So, you might ask, what do I now believe the role of the TL and the school library is? To synthesise such an abundance of discoveries and realisations into a short post is a challenge, but here it goes…

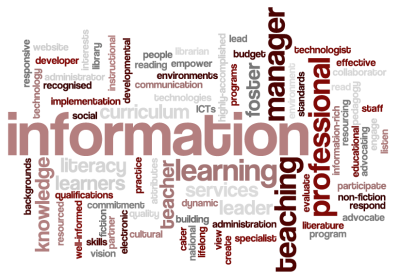

My narrow and naïve perception of the role of the TL was quickly deemed shallow as I was exposed to all of the responsibilities of and challenges faced by TLs (Herring, 2007; Lamb, 2011; Purcell, 2010; Valenza, n.d.; Hope, Kajiwara, & Liu, 2001; Lowe, 2000; Hallam & Partridge, 2005), as discussed in my blog entry from March 23, 2013. The presentation of such a complex role was overwhelming. Thankfully, at this time, I was introduced to Australia’s current standards (Australian School Library Association, 2004), which clearly defined for me an effective TL and what they should encompass in their practice through twelve Standards of Professional Excellence. These are valuable goals to which I will aspire.

It was disconcerting to find that the shallow views I held about the role of the TL were not uncommon, and were held by others within the subject together with some beyond the subject. Many believe that libraries are basically storehouses of information, and that TLs are not leaders or educators, but rather service providers who respond to students’ requests when necessary, when actually, the truth is quite the opposite. In order to counteract this stereotypical view, to present the reality, and to break down the barriers of invisibility, I discovered that TLs must be visible leaders in their schools, striving to gain support from the school as they collaborate with teachers, principals and community members in relation to their role and the library, and also by utilising evidence-based practice, in order to document the difference that they make in learning (Todd, 2003), as discussed in blog from April 15, 2013. My ignorance about the role of the TL was made clear in this area of student learning, as I was stunned with undeniable evidence that the excellent TL plays a critical role in supporting student learning, and can have a significant impact on student learning outcomes (Hay, 2005; Hay, 2006; Haycock, 2007; Lonsdale, 2003).

Then, just when I would have never imagined the role of the TL could become any deeper than I had already discovered it was, Assignment 2 (Part A) made known to me that in fact, it was. Not only are TLs responsible for impacting student learning outcomes, they are also responsible for empowering students from all walks of life to become effective citizens of an increasingly technological society, and ultimately, to achieve their personal, social, occupational and educational goals (Garner, 2006). Through the teaching of Information Literacy (IL) (using models such as Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process (ISP) (1991; 2004; 2008) and the New South Wales Information Skills Process model (NSW DEC, 2007), students are inspired to become critical thinkers, enthusiastic readers, practiced researchers, and appropriate users of information resources (Purcell, 2010). These skills learned are ones they will carry with them as they move from school to adulthood, to employment, to further education, vocational training and community members (O’Connell, 2012a; O’Connell, 2012b; Lowe, 2000). Can the role of the TL be any more important than this?

This is an overview of a myriad of areas in which my understanding of the role of the TL has been transformed during this subject. In closing, my final words of ETL401- This subject has been of great benefit to me, not only as a future TL, but also a classroom teacher and a member of a school community. Although the learning curve was often steep (being a Master’s Level subject), the hike uphill was an invaluable experience, and I will strive to carry with me into my teaching the knowledge, skills and understandings gained.

References

Australian School Library Association. (2004, December). Standards of professional excellence for teacher librarians. Retrieved March 16, 2013, from Australian School Library Association: http://www.asla.org.au/policy/standards.aspx

Garner, S. D. (2006). High-Level Colloquium on Information Literacy and Lifelong Learning. Alexandria, Egypt: United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), National Forum on Information Literacy (NFIL) and the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA).

Hallam, G. C., & Partridge, H. L. (2005). Great expectations? Developing a profile of the 21st century library and information student: a Queensland University of Technology case study. Libraries – a voyage of discovery. International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) World Library and Information Congress (pp. 14-18). Oslo: 71st IFLA General Conference and Council.

Hay, L. (2005). Student learning through Australian school libraries Part 1: A statistical analysis of student perceptions . Synergy , 3 (2), 17-30.

Hay, L. (2006). Student learning through Australian school libraries Part 2: What students define and value as school library support. Synergy , 4 (2), 27-38.

Haycock, K. (2007). Collaboration: critical success factors for student learning. School Libraries Worldwide , 13 (1), 25-35.

Herring, J. (2007). Teacher librarians and the school library. In S. Ferguson (Ed.), Libraries in the twenty-first century: Charting new directions in information (pp. 27-42). Wagga Wagga, NSW: Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University.

Hope, C. B., Kajiwara, S., & Liu, M. (2001). The Impact of the Internet. The Reference Librarian , 35 (74), 13-36.

Kuhlthau, C. (1991). Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science , 42 (5), 361-371.

Kuhlthau, C. (2004). Learning as a process. In Seeking meaning : a process approach to library and information services (2nd ed., pp. 13-27). Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhlthau, C., Heinström, J., & Todd, R. J. (2008). The ‘information search process’ revisited: is the model still useful? Information Research , 13 (4).

Lamb, A. (2011). Bursting with potential: Mixing a media specialist’s palette. Techtrends: Linking Research & Practice To Improve Learning , 55 (4), 27-36.

Lonsdale, M. (2003). Impact of School Libraries on Student Achievement: A review of the research. Victoria: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Lowe, C. A. (2000). The Role of the School Library Media Specialist in the 21st Century. ERIC Clearinghouse on Information and Technology. Syracuse: ERIC.

NSW Department of Education and Training. (2007). Information skills in the school: engaging learners in constructing knowledge. Sydney, NSW: School Libraries and Information Literacy Unit.

O’Connell, J. (2012b). Learning without frontiers: School libraries and meta-literacy in action. Access , 26 (1), 4-7.

O’Connell, J. (2012a). Change has arrived at an iSchool library near you. In Information literacy beyond library 2.0 (pp. 215-228). London: Facet.

Purcell, M. (2010). All Librarians Do Is Check Out Books, Right? A Look at the Roles of a School Library Media Specialist. Library Media Connection , 29 (3), 30-33.

Todd, R. (2003). Irrefutable evidence: How to prove you boost student achievement. School Library Journal .

Valenza, J. (n.d.). Flickr. Retrieved March 17, 2013, from What Do TLs Teach?: http://www.flickr.com/photos/78154370@N00/5761280491/sizes/l/in/photostream/